Quotes

Read, cite, and share quotes from major reports regarding biodiversity loss.

Biodiversity is essential to our very existence, supporting our water and food supplies, our health and the stability of the climate. Biodiversity is declining in all regions of the world and at all spatial scales, impacting ecosystem functioning, water availability and quality, food security and nutrition, human, plant and animal health and resilience to the impacts of climate change.

Biodiversity and functioning ecosystems play a vital role in providing nature’s contributions to people, including regulating the climate and nutrient and hydrological cycles that are essential for providing sufficient and clean water, sustaining food systems, regulating pests and pathogens, improving physical and mental health, providing traditional and modern medicines and supporting cultural identities. However, for the past 30 to 50 years, all the assessed indicators show biodiversity declines between 2 and 6 per cent per decade.

Biodiversity loss and climate change interact and compound each other, negatively impacting ecosystem resilience and all the other nexus elements. Functioning and resilient ecosystems contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation, such as by buffering extreme weather events and acting as a carbon sink. In contrast, biodiversity loss reduces the ability of ecosystems, such as forests and oceans, to sequester carbon, thereby increasing greenhouse gas concentrations and accelerating climate change.

Biodiversity loss reduces water availability, increases pathogen emergence and exacerbates some forms of water pollution, undermining human, plant and animal health. Biodiversity supports resilient and productive marine, coastal and freshwater fisheries, as well as agricultural systems through pollination, pest control and soil health.

However, unsustainable agricultural practices have contributed to biodiversity loss, greenhouse gas emissions, and air, water and land pollution, with some systems, such as fisheries, approaching tipping points.

Increased food production has generally improved human health, helping to lower child mortality and lengthen human lifespans. Sufficient and healthy food, including a variety of fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains and nuts, contributes to a sustainable healthy diet.7 However, a lack of agrobiodiversity and diet diversity continues to limit these health gains, especially for people with lower incomes and those in vulnerable situations.

In the past 50 years, global trends in a wide range of indirect drivers have intensified direct drivers of biodiversity loss and caused negative outcomes for biodiversity, water availability and quality, food security and nutrition, and health, and contributed to climate change.

Global trends in indirect drivers of biodiversity loss, including economic, demographic, cultural and technological change (such as overconsumption and waste), have led to intensified trends in direct drivers (such as landand sea-use change, unsustainable exploitation, climate change, pollution and invasive alien species) in terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystems.

This is made worse by fragmented governance of biodiversity, water, food, health and climate change, with different institutions and actors8 often working on disconnected and siloed policy agendas, resulting in conflicting objectives and duplication of efforts.

These direct and indirect drivers interact with each other and cause cascading impacts among the nexus elements. For example, increases in unsustainable food production have been associated with land conversion and the expansion of unsustainable agricultural practices, driven by affluence in particular. Such practices have led to biodiversity loss, reduced water availability and quality, increases in the risk of pathogen emergence and increases in greenhouse gas emissions.

Overharvesting, overfishing and unsustainable exploitation and production activities on land and sea also degrade freshwater and marine systems that are crucial for water cycles, food security and climate change mitigation.

Societal, economic and policy decisions that prioritize short-term benefits and financial returns for a small number of people while ignoring negative impacts on biodiversity and other nexus elements lead to unequal outcomes for human well-being. Existing governance approaches have often failed to account for and address these negative impacts in degrading nature, with the negative impacts disproportionately affecting the well-being of some as compared with others.

Current economic and financial systems invest $7 trillion per year in activities that damage biodiversity and other nexus elements. Dominant economic systems can result in unsustainable and inequitable economic growth and prioritize only a limited set of nature’s contributions to people (e.g., water and food) while not accounting for diverse values of nature.

Continuation of current trends in direct and indirect drivers will result in substantial negative outcomes for biodiversity, water availability and quality, food security and human health, while exacerbating climate change. Scenarios that prioritize objectives for a single element of the nexus without regard to other elements (i.e., solely for biodiversity, water, food, human health or climate change) will result in trade-offs across the nexus.

Nexus-wide benefits with positive outcomes for people and nature are feasible in the future, but achieving the highest levels of positive outcomes across all nexus elements is challenging. Scenarios that achieve balanced benefits across the nexus elements tend to include response options that effectively conserve, restore and sustainably use and manage ecosystems, reduce pollution across terrestrial, freshwater and marine realms and support adoption of sustainable healthy diets and climate change mitigation and adaptation

Positive scenarios show outcomes that include halting and reversing biodiversity loss, improving water availability and quality and food security, improving human health outcomes and slowing the rate of climate change. These scenarios include integrated and timely adoption of multiple response options that do not focus solely on a single nexus element but include combinations of effective biodiversity conservation (in terrestrial, freshwater and marine systems), ecosystem restoration and sustainable healthy diets.

Scenarios focused on synergies among biodiversity, water, food, human health and climate change have more beneficial outcomes for global policy goals, such as the Sustainable Development Goals. Siloed policy approaches and actions that prioritize a single nexus element limit the achievement of benefits across policy goals

Numerous highly synergistic response options are already available to actors in multiple sectors for sustainably managing biodiversity, water, food, health and climate change. Response options not typically focused on biodiversity can often have greater benefits for biodiversity than those specifically designed as such. Response options, when implemented at appropriate scales and contexts, provide many benefits to different degrees across the nexus elements, and many are low cost.

Response options can facilitate or impede each other, leading to potential synergies and tradeoffs among them. The efficacy of response options in realizing nexus-wide benefits can be enhanced by implementing them together or sequentially, as some response options enable others or amplify their benefits

Response options can strongly advance global policy efforts, including the Sustainable Development Goals, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and the Paris Agreement, to achieve just and sustainable futures. Response options designed to benefit multiple nexus elements support multiple goals and targets across global policy frameworks, strengthening synergies and alignment among them.

Transforming current siloed modes of governance through more integrative, inclusive, equitable, accountable, coordinated and adaptive approaches enables successful implementation of response options to manage the nexus elements, and their associated direct and indirect drivers, in an integrated manner, with benefits for people and nature now and into the future.

Gaps in finance to meet biodiversity needs amount to $0.3 trillion to $1 trillion per year, and additional investment needs to meet the Sustainable Development Goals most directly related to water, food, health and climate change come to at least $4 trillion per year. Urgent action to transform values and structures and address the dominance of a narrow set of interests within economic and financial systems can enable increased investments for biodiversity and the other nexus elements.

Nexus governance approaches, decisionmaking and capacity-strengthening can be enhanced through a series of deliberative steps and actions, informed by diverse evidence. A road map for nexus action can be used by a wide range of actors in multiple sectors to identify problems and shared values in order to work collaboratively towards solutions to help achieve just and sustainable futures aligned with global policy frameworks. Tools and methods facilitating a holistic understanding of nexus elements can increase knowledge and improve cooperation and decision-making.

Citation

IPBES (2024). Summary for Policymakers of the Thematic Assessment Report on the Interlinkages among Biodiversity, Water, Food and Health of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. McElwee, P. D., Harrison, P. A., vanHuysen, T. L., Alonso Roldán, V., Barrios, E., Dasgupta, P., DeClerck, F., Harmáčková, Z. V., Hayman, D. T. S., Herrero, M., Kumar, R., Ley,D., Mangalagiu, D., McFarlane, R. A., Paukert, C., Pengue, W. A., Prist, P. R., Ricketts, T. H., Rounsevell, M. D. A., Saito, O., Selomane,O., Seppelt, R., Singh, P. K., Sitas, N., Smith, P., Vause, J., Molua, E. L., Zambrana-Torrelio, C., and Obura, D. (eds.). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13850289

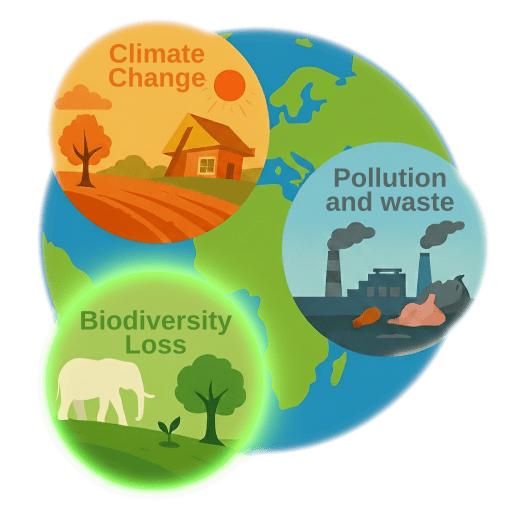

The triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution poses a growing threat to the environment and the economy. While each of these challenges is pressing, interlinkages can magnify their cumulative impact while creating opportunities for synergistic action.

This Environmental Outlook aims to inform an integrated policy approach that accounts for common drivers, pressures and mutually reinforcing impacts of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution.

Environmental pressures are primarily driven by growth in specific economic sectors, spurred by socio-economic trends of population and economic growth. Agriculture will remain the main driver of land use change, responsible for 87% of land conversion. Intensification in agricultural production will mitigate but not prevent an increase in agricultural land. Fossil fuel use is projected to increase by 16% (from 466 t541 exajoules), with a shift towards natural gas. Amid ongoing electrification of the energy system, renewables power generation is projected tmore than double (from 80 t209 exajoules). Primary materials use is projected tincrease by roughly half (from 96 t145 Gigatonnes) while global water withdrawal is expected tincrease by 17%.

Technological and behavioural changes will enable some decoupling between environmental pressures and economic growth. However, these factors are projected to slow – but not halt – global demand growth of energy, food, materials and water.

Environmental pressures underpinning the triple planetary crisis are set to intensify along several dimensions. As environmental pressures rise, climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution are set to worsen over time and reinforce each other.

Modelling projections suggest that, under current policies, between 2020 and 2050: Global mean temperatures will continue to increase (from 1.2°C in 2020 to 2.1°C in 2050 above pre-industrial levels). Climate change is also projected to become the main driver of biodiversity loss before mid-century. The terrestrial mean species abundance index is projected to further decline (from 59.7 to 56.5). This is equivalent to the conversion of pristine habitat of more than 4 million km2 into an area where all the original species have been lost.

As regards pollution, the situation is mixed. Concentrations of particulate matter and ozone are projected to decline in most regions, driven by reduction in emissions of precursor gases. Sulphur dioxide emissions, for instance, are projected to significantly decline in all regions (with a 64% decrease globally). This decline, however, will accelerate warming due to the cooling effect of sulphur dioxide. Pollutant emissions to water and soil are projected to continue to increase, not least ammonia (with a 43% increase globally). Mismanaged plastic waste is projected to increase from 83 to 138 million tonnes, leading to an increase in global plastic leakage to the environment from 22 to 37 million tonnes.

There is ample potential for more integrated policies, but much more needs to be done. The linkages among climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution may suggest that addressing one challenge automatically helps tackle the other two. However, interactions between policies underscore the potential for synergies and trade-offs. Failing to consider these interactions can result in policy gaps and missed opportunities from more integrated action.

A first-of-its-kind stocktake of 20 national documents across 10 countries (Argentina, Australia, Canada, the People’s Republic of China, France, India, Indonesia, Japan, Peru, and Uganda) finds that: Biennial Transparency Reports and National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans include relatively extensive discussions on the linkages between climate change and biodiversity in terms of their biophysical impacts; Considerations of how climate change and biodiversity loss might affect the severity and extent of pollution are largely lacking; Policies targeted at managing trade-offs – particularly for pollution – are sparse.

Deep dives demonstrate opportunities for a more integrated approach for renewable energy expansion, management and expansion of protected areas, air pollution control and nutrient management.

Six policy levers can support the development of more synergistic responses.

Three foundational levers can lay the groundwork for integrated policy approaches to fundamentally address the triple planetary crisis and its underlying drivers.

Addressing key gaps in research and assessment through better targeting of research funding and by leveraging (inter)national scientific assessment processes on climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution.

Strengthening the consideration of interlinkages between these three challenges in national reporting frameworks for multilateral environmental agreements. In addition, developing national approaches to tackle pollution comparable to those for climate change and biodiversity can help prevent blind spots.

Aligning finance and resource allocation towards jointly addressing the challenges posed by the triple planetary crisis. Synergies can be promoted by embedding interlinkages in multilateral environmental and development finance, using national budgeting processes to incentivise collaboration across ministries and ensuring support measures are well-targeted.

Complementarily, specific considerations for clean energy, material resources and food systems can help enhance synergies and minimise the risks for trade-offs, while also addressing social and distributional concerns such as job and income losses, affordability, and access to food and energy.

Better assessing and managing unintended impacts of the clean energy transition so that the adverse biodiversity and pollution impacts do not become an impediment to accelerated renewable energy expansion. Spatial planning and regulatory tools such as licensing and permitting, as well as better management of end-of-life fates, can help limit potential adverse impacts of renewables expansion on biodiversity and pollution control objectives.

Transitioning to a more resource-efficient and circular economy to address the significant environmental impacts of resource use on the triple planetary crisis. Action is needed across the materials lifecycle, including mainstreaming the circular economy within other policy domains, exploiting synergies with resource-intensive sectors, strengthening and realigning incentives, and leveraging demand-side interventions.

Policies are needed to reduce the environmental footprint of food production and consumption. This is critical to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, mitigating ecosystem degradation from agricultural land use expansion and intensification, and alleviating nutrient pollution. Governments can consider revising regulations and safeguards with an aim to reduce emissions, shift diets and decrease food loss and waste.

Citation

OECD (2025), Environmental Outlook on the Triple Planetary Crisis: Stakes, Evolution and Policy Linkages, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/257ffbb6-en.

Despite global efforts and calls for action, our planet has already entered into uncharted territory, facing global environmental crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, land degradation and desertification, and pollution and waste.

These interconnected crises, which are undermining human well-being and primarily caused by unsustainable systems of production and consumption, reinforce and exacerbate each other and need to be addressed together.

The situation is worsening: The rate of global warming is likely to be higher than the central estimates of previous IPCC projections, increasing the risk of irreversibly passing several climate tipping points1 within the next few decades. These include major shifts in ocean circulation, accelerated ice sheet loss, widespread permafrost thaw, forest die-back, and collapse of coral reef ecosystems.

One million of an estimated eight million species are threatened with extinction, some within decades. The populations of many more species are in decline, and their genetic diversity is being significantly eroded.

Between 20 and 40 per cent of land area was estimated to be degraded in 2022. Between 2015 and 2019, at least 100 million hectares (the size of Ethiopia or Colombia) of fertile and productive land were degraded annually worldwide.

Annual solid waste currently exceeds 2 billion tonnes and, given current trends, is projected to increase to 3.8 billion tons by 2050.

These environmental crises are causing substantial economic and social damage, including to infrastructure, transport, and basic services, harming jobs, livelihoods, economic growth and security, and undermining human health and well-being, food, energy and water security for all people, with disadvantaged populations being disproportionally affected. These crises are already reversing socioeconomic development achievements by increasing poverty and inequalities, and decreasing life expectancy. They can no longer be viewed as simply environmental issues; they are also economic, development, governance, security, social, moral, and ethical issues

Most of the internationally agreed (or adopted) environmental goals and targets are unlikely to be met with existing policies and practices, including those from the UNFCCC, Paris Agreement, the CBD, Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, and the UNCCD Strategic Framework 2018-2030, as well as World Health Organization (WHO) pollution standards.

Rising global resource consumption, including materials, energy, water and food, is primarily driven by increasingly resource-intensive lifestyles, especially in high-income countries, along with economic growth, demographic change and urbanization.

This increasing demand is being met using environmentally unsustainable production and consumption in the context of the current economic, financial, and governance systems, which themselves are unfit to meet these challenges sustainably.

These lead to the ever-increasing pressures from land-use change, resource use and exploitation, emissions of greenhouse gases and pollutants, and invasive alien species. Collectively, these are the underlying causes of the interconnected global environmental crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, land degradation and desertification, and pollution and waste.

Transformative solution pathways are possible – whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches at scale and pace can enable environmental goals to be met and provide social and economic benefits.

Achieving the internationally agreed (or adopted) environmental goals and targets requires transformation of the economic and financial, materials/waste, energy, and food systems – the human systems – and transformation of the way the environment system is managed for sustainability and resilience.

The GEO-7 scenario analysis shows that internationally agreed (or adopted) environmental goals can still be achieved, but will require unprecedented action. There are multiple pathways to do so, with benefits for people and planet. This requires combining coherent and coordinated transformative solutions within and across systems – economic and financial, materials/waste, energy, food, and environment – and well-being and environmental goals, to minimize potential trade-offs and take advantage of synergies.

A transformation framework is essential for the formulation and strategic implementation of solution pathways across systems, regions and scales. Solution pathways need to focus on system-wide transformations, identifying what needs to be developed, phased out, avoided, and preserved. They should articulate near- and long-term solutions, anticipate and reduce uncertainties, involve a plurality of actors and perspectives, and explicitly address the political nature of change.

There is a rapidly narrowing window of opportunities to successfully embrace and implement the solutions needed to transform the systems. Governments and intra- and intergovernmental organizations, working with the private sector, financial institutions, academia and civil society, need to: co-produce policies and solution pathways; develop and deploy appropriate technologies; provide the necessary level of financing; and motivate and accelerate institutional, social and cultural changes.

These need to be achieved at an unprecedented pace, scale, level of integration, and depth, while reforming existing powers, such as vested interests, and economic structures that perpetuate inequalities. While some progress is being made, it is not occurring at the pace and scale needed.

The economic benefits of action exceed the costs of transformation, as the damages from the global environmental crises will become increasingly severe over the coming decades. The overall macroeconomic annual benefits of transformation are estimated to begin around 2050 and increase to approximately US$20 trillion per year by 2070, and over US$100 trillion per year by 2100, accounting for more than 25 per cent of projected global GDP in 2100.

Achieving environmental goals, alongside social and economic benefits, requires a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach. This involves identifying and capitalizing on solutions that benefit multiple systems simultaneously, and are just and equitable, ensuring participation of all agents of change, such as actors and networks of actors. It also involves changing attitudes and behaviours, reforming existing national and multilateral governance structures and taking into account diverse world views and knowledge systems

Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ knowledge, values, and ways of being contribute to transformations towards sustainable and just futures. They offer concepts of humannature relations based on ethics of care and ways of organizing economies that take a holistic approach to well-being. Drawing on sustainable stewardship practices and adaptation strategies, Indigenous Knowledge and Local Knowledge can provide concrete guidance on actions relating to care of territories and life, as well as in relation to energy, food, governance and economies.

Transformation of the economic and financial systems will unlock transformations in the materials/waste, energy, and food systems, and improve environmental management.

Transformation of the economic and financial systems is a prerequisite for transforming the other systems, including: phasing out and repurposing environmentally harmful subsidies, of about US$1.5 trillion per year from energy, food and mining; internalizing social and environmental externalities into the prices of goods and services of about US$45 trillion per year from energy and food systems; moving beyond traditional measures of economic activity, and specifically gross domestic product (GDP) as it is conventionally measured, by including natural capital and human well-being in decision-making; and aligning financial flows with international environmental goals to transform the energy, materials/waste and food systems.

Transforming the materials/waste system requires implementing a global circular economy, including: designing out waste from production and consumption (e.g., in energy, food and water systems); shifting investments to deliver circularity in the economy, production and consumption; developing effective markets for secondary materials; creating a transparent global trade system for circular goods and services; and inclusive societal transformation towards sustainable lifestyles.

Transforming the global energy system requires a multifaceted approach that simultaneously addresses energy access and poverty and aligns with internationally agreed (or adopted) environmental goals and targets, including: diversifying energy production, including increasing use of renewable energy technologies, e.g., solar and wind, while simultaneously accelerating the phasing out of unabated fossil fuels; electrifying final energy services in transport, industry, housing and agriculture promoting efficient production and distribution; incentivizing demand-side management practices; and ensuring the sustainability of critical energy transition minerals.

Transforming the food system requires actions from policymakers, regulators, the food industry, the financial sector, farmers, researchers, communities and individuals, including: shifting to healthy and sustainable diets, including greater consumption of plant-based foods; adopting more sustainable and resilient food production practices; reducing food losses and waste and enhancing circularity across food systems; accelerating the development and uptake of novel alternative proteins, such as cultivated meat; and reforming food markets and trade, e.g., diversifying agribusiness supply chains and incentivizing environmentally responsible practices.

Improved management of the environment system for sustainability and resilience requires actions, including: protecting, conserving and restoring ecosystems and biodiversity, in conjunction with sustainable land management practices; adopting adaptive governance to safeguard the rights, access and benefits of Indigenous Peoples over their traditional lands, and draw on their knowledge; embracing the widescale implementation of nature-based solutions, to restore and maintain healthy socio-ecological systems; and ensuring the emerging bioeconomy is circular and sustainable.

The global environmental crises are adversely affecting every region of the world, albeit with wide variability, curtailing socioeconomic development, with the most severe consequences being experienced by the most vulnerable and disadvantaged populations. Within each region, sub-regional differences in vulnerability, capacity, and priorities should be recognized when tailoring transformation pathways.

Regions are interlinked through human and natural systems driven by processes such as trade, investment, tourism, migration, species invasion, and ecosystem services flows, which can have benefits, such as international trade, as well as adverse impacts, for instance, the exploitation of labour and natural resources.

As the systems transform regionally, these dynamics can change. The solution pathways presented in GEO-7 for transforming the systems and their implications are specific to each region, which accounts for their common and differentiated but specific priorities. The identified levers of action are specific to the system being transformed, the underlying conditions and the priorities of the regions.

Tailored solution pathways and system transformations are needed to address issues specific to each region or country that consider their sociocultural, economic, development, environmental, governance and financial circumstances, as well as issues common to all regions.

Recognizing that all countries care about sustainable economic growth, high-income countries can more easily adopt ambitious green policies, reduce resource consumption, acknowledge the principle of common but differentiated responsibility, halt the export of negative environmental impacts, and leverage global sustainability through finance and technological capacity. Middle-income countries can embrace innovative infrastructure development and green policies. Low-income countries can overcome challenges such as hunger and poverty, improve livelihoods, build climate-resilient communities and infrastructure, while reducing emissions by leapfrogging outdated technologies and leveraging targeted investments and international support.

Citation

United Nations Environment Programme (2025). Global Environment Outlook 7 Executive Summary: A future we choose – Why investing in Earth now can lead to a trillion-dollar benefit for all. Nairobi. https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/49015.

Transformative change for a just and sustainable world is urgent, necessary and challenging but possible, to halt and reverse biodiversity loss and safeguard life on Earth. It is required to respond to global environmental challenges and crises, including biodiversity loss, climate change and pollution.

Biodiversity is fundamental to the systems4 underpinning life and good quality of life and many of these systems are now at risk.

Transformative change that matches the scope, scale, speed and depth necessary to maintain life on this planet calls for new understandings and strategic approaches that yield positive results for biodiversity and nature. Drawing on a rapidly growing body of literature and informed by evidence from diverse scientific disciplines and different knowledge systems, the transformative change assessment recognizes that a simple system-wide reorganization of constituent elements is not enough.

To achieve the breadth, depth and dynamics of system reorganization described26 in the IPBES Values Assessment it is important to address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss and nature’s decline in a manner consistent with key guiding principles of transformative chang

Transformative change for a just and sustainable world is urgent and necessary to address the global interconnected crises related to biodiversity loss, nature’s decline and the projected collapse of key ecosystem functions. Delaying action to achieve global sustainability is costly compared to the benefits of taking action now.

Transformative change is defined as fundamental, system-wide shifts in views, structures and practices. Deliberate transformative change for a just and sustainable world shifts views, structures and practices in ways that address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss and nature’s decline. At the same time, it remains important to recognise and strengthen views, structures and practices that are aligned with generating a just and sustainable world, such as those of many Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

Four key principles11 are responsive to and address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss and nature’s decline and guide the process of deliberate transformative change. These principles are equity and justice; pluralism and inclusion; respectful and reciprocal human-nature relationships; and adaptive learning and action.

Transformative change for a just and sustainable world faces challenges that are systemic, persistent and pervasive. Systemic challenges manifest as barriers that impede or prevent transformative change and reinforce the status quo.

Weaving together insights from diverse approaches and knowledge systems, including Indigenous and local knowledge, enhances strategies and actions for transformative change.

Transformative change is possible, and it is characterized by the quality and direction of change. Both small-scale and large-scale changes contribute to transformative change for a just and sustainable world when they address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss and nature’s decline.

Transformative changes in sectors that heavily contribute to biodiversity loss13, including agriculture and livestock, fisheries, forestry, infrastructure, mining and fossil fuel sectors are crucial and urgent for advancing global sustainability, delivering social benefits to reach the 2050 Vision for Biodiversity (Strategy 2)

Transformative change strategies include transforming dominant economic and financial191 paradigms so that they prioritize nature and social equity over private interes

Shifting dominant societal views and values to recognize and prioritize human-nature interconnectedness is a powerful strategy for transformative change. These shifts can be facilitated through cultural narratives and by changing dominant social norms, facilitating transformative learning processes, co-creating new knowledge and weaving different knowledge systems, worldviews and values that recognize human-nature interdependencies and ethics of care.

Transformative change is system-wide, therefore, to achieve it requires a whole-of-society and whole-of-government approach that engages all actors and sectors in visioning and contributing collaboratively to transformative change.

Governments are powerful enablers of transformative change when they foster policy coherence, enact and enforce stronger regulations to benefit nature and nature’s contributions to people in policies and plans (regulations, taxes, fees, tradable permits) across different sectors, deploy innovative economic (including financial) and fiscal tools, eliminate, phase out or reform environmentally harmful subsidies, and promote international cooperation.

Civil society organizations, by fighting against biodiversity loss and nature’s decline, point to the need for transformative change. Social mobilizations to pursue change, however, have often triggered responses that do not possess key aspects of transformative change. Civil society initiatives and environmental defenders have faced violence and rights violations. Protecting them supports transformative change.

Citation

IPBES (2024). Summary for Policymakers of the Thematic Assessment Report on the Underlying Causes of Biodiversity Loss and the Determinants of Transformative Change and Options for Achieving the 2050 Vision for Biodiversity of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. O’Brien, K., Garibaldi, L., Agrawal, A., Bennett, E., Biggs, O., Calderón Contreras, R., Carr, E., Frantzeskaki, N., Gosnell, H., Gurung, J., Lambertucci, S., Leventon, J., Liao, C., Reyes García, V., Shannon, L., Villasante, S., Wickson, F., Zinngrebe, Y., and Perianin, L. (eds.). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11382230

Over the past 50 years (1970–2020), the average size of monitored wildlife populations has shrunk by 73%, as measured by the Living Planet Index (LPI). This is based on almost 35,000 population trends and 5,495 species of amphibians, birds, fish, mammals and reptiles. Freshwater populations have suffered the heaviest declines, falling by 85%, followed by terrestrial (69%) and marine populations (56%).

At a regional level, the fastest declines have been seen in Latin America and the Caribbean – a concerning 95% decline – followed by Africa (76%) and the Asia and the Pacific (60%).

Declines have been less dramatic in Europe and Central Asia (35%) and North America (39%), but this reflects the fact that large-scale impacts on nature were already apparent before 1970 in these regions: some populations have stabilized or increased thanks to conservation efforts and species reintroductions.

Habitat degradation and loss, driven primarily by our food system, is the most reported threat in each region, followed by overexploitation, invasive species and disease. Other threats include climate change (most cited in Latin America and the Caribbean) and pollution (particularly in North America and Asia and the Pacific).

By monitoring changes in the size of species populations over time, the LPI is an early warning indicator for extinction risk and helps us understand the health of ecosystems.

When a population falls below a certain level, that species may not be able to perform its usual role within the ecosystem – whether that’s seed dispersal, pollination, grazing, nutrient cycling or the many other processes that keep ecosystems functioning.

Stable populations over the long term provide resilience against disturbances like disease and extreme weather events; a decline in populations, as shown in the global LPI, decreases resilience and threatens the functioning of the ecosystem.

The LPI and similar indicators all show that nature is disappearing at an alarming rate. While some changes may be small and gradual, their cumulative impacts can trigger a larger, faster change. When cumulative impacts reach a threshold, the change becomes self-perpetuating, resulting in substantial, often abrupt and potentially irreversible change. This is called a tipping point.

In the natural world, a number of tipping points are highly likely if current trends are left to continue, with potentially catastrophic consequences. These include global tipping points that pose grave threats to humanity and most species, and would damage Earth’s life-support systems and destabilize societies everywhere.

Global tipping points can be hard to comprehend – but we’re already seeing tipping points approaching at local and regional levels, with severe ecological, social and economic consequences:

Approaching climate, biodiversity and development goals in isolation raises the risk of conflicts between different objectives – for example, between using land for food production, biodiversity conservation or renewable energy.

With a coordinated, inclusive approach, however, many conflicts can be avoided and trade-offs minimized and managed. Tackling the goals in a joined-up way opens up many potential opportunities to simultaneously conserve and restore nature, mitigate and adapt to climate change, and improve human well-being.

To maintain a living planet where people and nature thrive, we need action that meets the scale of the challenge. We need more, and more effective, conservation efforts, while also systematically addressing the major drivers of nature loss. That will require nothing less than a transformation of our food, energy and finance systems.

The global food system is inherently illogical. It is destroying biodiversity, depleting the world’s water resources and changing the climate, but isn’t delivering the nutrition people need.

Food production is one of the main drivers of nature’s decline: it uses 40% of all habitable land, is the leading cause of habitat loss, accounts for 70% of water use and is responsible for over a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions.

The way we produce and consume energy is the principal driver of climate change, with increasingly severe impacts on people and ecosystems.

The energy transition must be consistent with the protection and restoration of nature. Without careful planning and environmental safeguards, hydropower development will increase river fragmentation, bioenergy development could drive significant land-use change, and transmission lines and mining for critical minerals could impact sensitive land, freshwater and ocean ecosystems. Careful planning is needed to select the right renewables in the right places, avoid negative impacts, and streamline energy development without diluting environmental safeguards.

Redirecting finance away from harmful activities and toward business models and activities that contribute to the global goals on nature, climate and sustainable development is essential for ensuring a habitable and thriving planet

Yet our current economic system values nature at close to zero, driving unsustainable natural resource exploitation, environmental degradation and climate change.

Money continues to pour into activities that fuel the nature and climate crises: private finance, tax incentives and subsidies that exacerbate climate change, biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation are estimated at almost US$7 trillion per year. The positive financial flows for nature-based solutions, in comparison, are a paltry US$200 billion

Filling these gaps demands a seismic shift at global, national and local levels to get finance flowing in the right direction, away from harming the planet and toward healing it

It is no exaggeration to say that what happens in the next five years will determine the future of life on Earth.

We have five years to place the world on a sustainable trajectory before negative feedbacks of combined nature degradation and climate change place us on the downhill slope of runaway tipping points. The risk of failure is real – and the consequences almost unthinkable.

Citation

WWF (2024) Living Planet Report 2024 – A System in Peril. WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

Four years have passed since the 2019 Global Sustainable Development Report was published and even then, the world was not on track to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Since 2019, challenges have multiplied and intensified.

The world has moved forward on some fronts, such as the deployment of zero-carbon technologies as one of many climate mitigation strategies. Progress has been halted in many areas, partly as a consequence of a confluence of crises – the ongoing pandemic, rising inflation and the cost-of-living crisis, and planetary, environmental and economic distress, along with regional and national unrest, conflicts, and natural disasters.

The resilience and well-being of planet, people, environment and ecosystems are degraded. A better future does not reston one source of security, but on all necessary securities, including geopolitical, energy, climate, water, food and social security. Strategies to embrace transformations, therefore, should be based on the principles of solidarity, equity and well-being, in harmony with nature.

In 2019, the previous Global Sustainable Development Report found that for some targets the global community was on track, but for many others the world would need to quicken the pace.

In 2023, the situation is much more worrisome owing to slow implementation and a confluence of crises. For Goals in which progress was too slow in 2019, countries have not accelerated enough, and for others, including food security, climate action and protecting biodiversity, the world is still moving in the wrong direction.

These crises are not independent events; they are intertwined through multiple environmental, economic and social strands, each fuelling the other’s intensities.

Generally, these indicate that on a business-as-usual pathway, the Goals will remain out of reach by 2030, or even 2050. Gains would be made in key areas including extreme poverty reduction and global and national income convergence. But progress would be minimal on targets relating to malnutrition and governance. At the same time, the world would regress in air pollution and associated health impacts, agricultural water use, relative poverty rates, food waste, greenhouse gas emissions, and biodiversity and nitrogen use.

The world is far off track on achieving the Sustainable Development Goals at the halfway point on the 2030 Agenda. But it is possible to actively improve future prospects for action and progress by 2030 and beyond. Leveraging scientific knowledge, strengthening governance for the Goals and unleashing the full potential of the Sustainable Development Goals framework for promoting sustainable development can make this happen. SDG interlinkages, and international spillovers and dependencies must be systematically considered.

Implementation of the Agenda 2030 requires the active mobilization of political leadership and ambition, and building societal support for policy shifts embracing transformations through meaningful consultation with stakeholders and effective participation.

Third, it puts forward key synergetic interventions in each of the six entry-points for sustainability transformation, to achieve coherence and equity, and ensure that advances in human well-being are not made at the expense of climate, biodiversity and ecosystems.

This report bridges science and practice to provide actionable knowledge, practical tools, and examples fora variety of actors, from policymakers in United Nations Member States to youth and community groups, from financiers to other industry partners, from donor agencies to philanthropies, and from academics to civil society groups.

Citation

Independent Group of Scientists appointed by the Secretary-General, Global SustainableDevelopment Report 2023: Times of crisis, times of change: Science for accelerating transformations to sustainabledevelopment, (United Nations, New York, 2023

Fast-forward to the present day, and much of our current scientific knowledge of global plant and fungal diversity comes from specimens hosted by the world’s herbaria and fungaria, of which there are more than 3,000. But despite this wealth of knowledge and collections, one might be surprised to learn that, to date, we have not been able to answer one of the most fundamental questions in plant and fungal diversity with confidence – namely, how many species are there globally and in different parts of the world?

The consequences of our insufficient knowledge on biodiversity and distribution are manifold. Scientists may have drawn biased – or possibly even incorrect – conclusions on the patterns and underlying drivers of diversity. Beyond the impacts of knowledge gaps and inaccuracies on efforts to answer fundamental scientific questions, there are serious implications for conservation given that several targets in the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, such as those related to protecting and restoring biodiverse habitats, rely on having robust biodiversity data.

Around the world, myriad Lifeforms have evolved to depend On each other in complex ways. This biodiversity, at scales from Single genes to entire ecosystems, Is essential for our existence.

Plants, in particular, provide us with food, materials, medicines and more. They regulate important planetary cycles that provide us with the air we breathe and water we drink, and contribute to our overall well-being.

If we are to safeguard life on Earth, we must end the current extinction crisis in which plant species are dying out at least 500 times faster than before humans existed.

But with limited time and resources, we need to know how best to conserve biodiversity to keep ecosystems diverse and functioning, while preserving species with the greatest potential for use by future human population.

Researchers measure biodiversity in different ways, including by considering the distinctiveness of species resulting from their evolutionary history.

Diverse evolutionary lineages underpin an ecosystem’s resilience to environmental change.

Traditionally, conservation has focused on species richness and endemism. However, phylogenetic diversity, which takes account of evolutionary history, is a more effective measure of capturing diversity and ensuring ecosystems remain resilient.

The maps show that phylogenetic diversity is more evenly distributed across the globe, so current conservation priorities may need to be rethought to ensure critical biodiversity is not lost.

32 plant data darkspots have been identified worldwide. Fourteen are within tropical Asia, nine within South America, six in temperate Asia, two in Africa, and one in North America.

They are the dark matter of botany – plant species that are yet to be scientifically named, described and mapped but which are estimated to make up 15% of the world’s flora. As well as being part of the global

With 77% of undescribed species predicted to be threatened with extinction (see Chapter 9), the race is on to find and conserve them.

Many species that are unknown to science are, in fact, well known to indigenous communities.

Iran is one of six plant diversity darkspots located within temperate Asia.

The largest knowledge gaps on plant diversity and distribution occur in Colombia.

New Guinea comes second in terms of knowledge gaps and is also the only country not to overlap with the current global Biodiversity Hotspots.

Madagascar and cape provinces have the greatest combined data gaps for Africa.

Overall, the work indicated that if recent trends in scientifically describing and mapping new plant species continue, current botanical collection may be insufficient to completely document the geographical distribution of all vascular plants in the near future.

And while the current Biodiversity Hotspot classification is regarded as a useful framework to guide biodiversity scientists and conservationists, the new research findings show that the Hotspots alone are not enough to inform collection priorities. Rather, in parallel with the findings outlined in Chapter 6, they indicate that considering plant diversity darkspots in conjunction with Hotspots would be a better approach going forward.

Citation

Antonelli, A., Fry, C., Smith, R.J., Eden, J., Govaerts, R.H.A., Kersey, P., Nic Lughadha, E., Onstein, R.E., Simmonds, M.S.J., Zizka, A., Ackerman, J.D., Adams, V.M., Ainsworth, A.M., Albouy, C., Allen, A.P., Allen, S.P., Allio, R., Auld. T.D., Bachman, S.P., Baker, W.J., Barrett, R.L., Beaulieu, J.M., Bellot, S., Black, N., Boehnisch, G., Bogarín, D., Boyko, J.D., Brown, M.J.M., Budden, A., Bureš, P., Butt, N., Cabral, A., Cai, L., Aguilar-Cano, J.A., Chang, Y., Charitonidou, M., Chau, J.H., Cheek, M., Chomicki, G., Coiro, M., Colli-Silva, M., Condamine, F.L., Crayn, D.M., Cribb, P., Cuervo-Robayo, A.P., Dahlberg, A., Deklerck, V., Denelle, P., Dhanjal-Adams, K.L., Druzhinina, I., Eiserhardt, W.L., Elliott, T.L., Enquist, B.J., Escudero, M., Espinosa-Ruiz, S., Fay, M.F., Fernández, M., Flanagan, N.S., Forest, F., Fowler, R.M., Freiberg, M., Gallagher, R.V., Gaya, E., Gehrke, B., Gelwick, K., Grace, O.M., Granados Mendoza, C., Grenié, M., Groom, Q.J., Hackel, J., Hagen, E.R., Hágsater, E., Halley, J.M., Hu, A.-Q,, Jaramillo, C., Kattge, J., Keith, D.A., Kirk, P., Kissling, W.D., Knapp, S., Kreft, H., Kuhnhäuser, B.G., Larridon, I., Leão, T.C.C., Leitch, I.J., Liimatainen, K., Lim, J.Y., Lucas, E., Lücking, R., Luján, M., Luo, A., Magallón, S., Maitner, B., Márquez-Corro, J.I., Martín-Bravo, S., Martins-Cunha, K., Mashau, A.C., Mauad, A.V., Maurin, O., Medina Lemos, R., Merow, C., Michelangeli, F.A., Mifsud, J.C.O., Mikryukov, V., Moat, J., Monro, A.K., Muasya, A.M., Mueller, G.M., Muellner-Riehl, A.N., Nargar, K., Negrão, R., Nicolson, N., Niskanen, T., Oliveira Andrino, C., Olmstead, R.G., Ondo, I., Oses, L., Parra-Sánchez, E., Paton, A.J., Pellicer, J., Pellissier, L., Pennington, T.D., Pérez-Escobar, O.A., Phillips, C., Pironon, S., Possingham, H., Prance, G., Przelomska, N.A.S., Ramírez-Barahona, S.A., Renner, S.S., Rincon, M., Rivers, M.C., Rojas Andrés, B.M., Romero-Soler, K.J., Roque, N., Rzedowski, J., Sanmartín, I., Santamaría-Aguilar, D., Schellenberger Costa, D., Serpell, E., Seyfullah, L.J., Shah, T., Shen, X., Silvestro, D., Simpson, D.A., Šmarda, P., Šmerda, J., Smidt, E., Smith, S.A., Solano-Gomez, R., Sothers, C., Soto Gomez, M., Spalink, D., Sperotto, P., Sun, M., Suz, L.M., Svenning, J.-C., Taylor, A., Tedersoo, L., Tietje, M., Trekels, M., Tremblay, R.L., Turner, R., Vasconcelos, T., Veselý, P., Villanueva, B.S., Villaverde, T., Vorontsova, M.S., Walker, B.E., Wang, Z., Watson, M., Weigelt, P., Wenk, E.H., Westrip, J.R.S., Wilkinson, T., Willett, S.D., Wilson, K.L., Winter, M., Wirth, C., Wölke, F.J.R., Wright, I.J., Zedek, F., Zhigila, D.A., Zimmermann, N.E., Zuluaga, A., Zuntini, A.R. (2023). State of the World’s Plants and Fungi 2023. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. DOI: https://doi.org/10.34885/wnwn-6s63

The causes of the global biodiversity crisis and the opportunities to address them are tightly linked to the ways in which nature is valued in political and economic decisions at all levels.

Unprecedented climate change and decline of biodiversity are affecting ecosystem functioning and negatively impacting people’s quality of life. An important driver of the global decline of biodiversity is the unsustainable use of nature, including persistent inequalities between and within countries, emanating from predominant political and economic decisions based on a narrow setof values (e.g., prioritizing nature’s values as traded in markets).

Despite the diversity of nature’s values, most policymaking approaches have prioritized a narrow set of values at the expense of both nature and society, as well as of future generations, and have often ignored values associated with indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ world-views.

The diversity of nature’s values in policymaking can be advanced by considering atypology of nature’s values that encompasses therichness of people’s relationships with nature.

Valuation processes can be tailored to equitably take into account the values of nature of multiple stakeholders in different decision-making contexts.

More than 50 valuation methods and approaches, originating from diverse disciplines and knowledge systems, are available to dateto assess nature’s values; choosing appropriate and complementary methods requires assessing trade-offs between their relevance, robustness and resource requirement.

Despite increasing calls to consider valuation in policy decisions, scientific documentation shows that less than 5 per cent of published valuation studies report its uptake in policy decisions.

Achieving sustainable and just futures requires institutions that enable a recognition and integration of the diverse values of nature and nature’s contributions to people.

Transformative change needed to address the global biodiversity crisis relies on shifting away from predominant values that currently over-emphasize short term and individual material gains, to nurturing sustainability-aligned values across society.

Working with a combination of four values- based leverage points (i.e., undertaking valuation, embedding values in decision-making, reforming policy and shifting societal goals) may catalyse transformation towards sustainable and just futures.

Information, resource (i.e., technical and financial) and capacity gaps hinder the inclusion of diverse values of nature in decision- making. Capacity-building and development, and collaborations among a range of societal actors, can help bridge these gaps.

Citation

IPBES (2022). Summary for Policymakers of the Methodological Assessment Report on the Diverse Values and Valuation of Nature of theIntergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Pascual, U., Balvanera, P., Christie, M., Baptiste, B.,González-Jiménez, D., Anderson, C.B., Athayde, S., Barton, D.N., Chaplin-Kramer, R., Jacobs, S., Kelemen, E., Kumar, R., Lazos, E.,Martin, A., Mwampamba, T.H., Nakangu, B., O’Farrell, P., Raymond, C.M., Subramanian, S.M., Termansen, M., Van Noordwijk, M., andVatn, A. (eds.). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6522392

Most of humanity has historically fought against nature, draining wetlands, razing forests for urban development, canalising rivers and introducing monocultures with heavy use of fertilisers and pesticides. The future will have to look fundamentally different by working with nature if we are to reverse the severe loss of biodiversity, tackle the climate crisis and restore a billion hectares of healthy ecosystems that have been lost over the last few decades.

With sufficient finance, nature-based solutions (NbS) provide the means to cost-effectively reach climate, biodiversity and land degradation neutrality targets, particularly if investments simultaneously contribute to biodiversity, climate and restoration targets. This “double” or “triple” win potential is particularly alluring given the current economic situation.

Delayed action is no longer an option in the face of the devastating effects of climate change, the extinction crisis and severe land degradation globally. Politicians, business and finance leaders and citizens globally must transform their relationship with nature to work with it rather than against it.

If we rapidly double finance flows to NbS, we can halt biodiversity loss (measured through the Biodiversity Intactness Index below), significantly contribute to reducing emissions (5 GtCO2/year by 2025 further rising to 15 GtCO2/year by 2050 in the 1.5°C scenario) and restore close to 1 billion ha of degraded land.

Private sector investment in NbS must increase by several orders of magnitude in the coming years from the current US$26 billion per year, which represents only 17 per cent of total NbS investment.

Government expenditure on environmentally harmful subsidies to fisheries, agriculture and fossil fuels is estimated at US$500 billion to 1 trillion per year, which is three to seven times greater than public and private investments in NbS. These flows severely undermine efforts to achieve critical environmental targets.

Investment in marine NbS constitutes only 9 per cent of total investment in NbS, which is very low given the role of theoceans in climate mitigation and supporting adaptation, food security and biodiversity conservation.

Governments need to lock in critical targets on biodiversity loss, take urgent action to raise ambition and implement emissions reduction targets in line with the Paris Agreement and action land restoration commitments. These targets must be underpinned by broad based resource mobilisation from all sources. Public and private actors need to mobilise the necessary finance and close the finance gap while governments anchor targets in national regulation/legislation.

Increase direct finance flows to NbS through public domestic expenditure, nature-focused Official Development Assistance (ODA), ensuring that multilateral development banks (MDBs) and development finance institutions (DFIs) prioritise green finance, and providing regulation and incentives for private sector investment, particularly in nature markets and sustainable supply chains.

Companies in the real economy and financial institutions need to transition to “net zero, net positive” and equitable business models in a time-bound manner with short-term targets.

Public and private sector efforts to scale up NbS investments need to integrate just transition principles, safeguarding human rights. This includes providing social protection, land rights and decent working conditions and the participation of local and indigenous communities, including women and otherm arginalised and vulnerable groups.

Citation

United Nations Environment Programme (2022). State of Finance for Nature. Time to act:Doubling investment by 2025 and eliminating nature-negative finance flows. Nairobi. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/41333

Today we face the double, interlinked emergencies of human-induced climate change and the loss of biodiversity, threatening the well-being of current and future generations. As our future is critically dependent on biodiversity and a stable climate, it is essential that we understand how nature’s decline and climate change are connected.

Land-use change is still the biggest current threat to nature, destroying or fragmenting the natural habitats of many plant and animal species on land, in freshwater and in the sea. However, if we are unable to limit warming to 1.5°C, climate change is likely to become the dominant cause of biodiversity loss in the coming decades.

Tracking the health of nature over almost 50 years, the Living Planet Index acts as an early warning indicator by tracking trends in the abundance of mammals, fish, reptiles, birds and amphibians around the world. In its most comprehensive finding to date, this edition shows an average 69% decline in the relative abundance of monitored wildlife populations around the world between 1970 and 2018.

Latin America shows the greatest regional decline in average population abundance (94%), while freshwater species populations have seen the greatest overall global decline (83%).

We know that transformational change – game-changing shifts– will be essential to put theory into practice. We need system-wide changes in how we produce and consume, the technology we use, and our economic and financial systems. Underpinning these changes must be a move from goals and targets to values and rights, in policy-making and in day-to-day life.

A nature-positive future needs transformative - game changing - shifts in how we produce, how we consume, how we govern, and what we finance.

Achieving net-zero loss for nature is certainly not enough; we need a nature- or net-positive goal to restore nature and not simply halt its loss. Firstly, because we have lost and continue to lose so much nature at such a speed that we need this higher ambition.

Climate change and biodiversity loss are not only environmental issues, but economic, development, security, social, moral and ethical issues too – and they must therefore be addressed together along with the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Climate change and biodiversity loss are not only environmental issues, but economic, development, security, social, moraland ethical issues too.

Unless we conserve and restore biodiversity, and limit human-induced climate change, almost none of the [17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)] can be achieved – in particular food and water security, good health for everyone, poverty alleviation, and a more equitable world.

Everyone has a role to play in addressing these emergencies; and most now acknowledge that transformations aren eeded. This recognition now needs to be turned into action.

Human-driven global warming is changing the natural world, driving mass mortality events as well as the first extinctions of entire species. Every degree of warming is expected to increase these losses and the impact they have on people.

Warming is also changing how ecosystems function, putting into motion ecological processes that, themselves, in time cause more warming: this process is called a ‘positive climate feedback’.

Increases in wildfires, trees dying due to drought and insectoutbreaks, peatlands drying and tundra permafrost thawing, all release more CO₂ as dead plant material decomposes or is burned. This is starting to transform systems that have historically been solid carbon sinks into new carbon sources.

Once these ecological processes reach a tipping point they will become irreversible and commit our planet to continue warming at a very high rate.

Forests are critical for stabilising our climate, but deforestation threatens this vital function as well as other ecosystem services including buffering against the impact of heatwaves, and providing freshwater to agricultural lands.

Ecological connectivity is severely threatened by the destruction and degradation of nature that fragments habitats. To counter this, connectivity conservation is rapidly emerging as a solution to restore the movement of species and the flow of natural processes.

Around the globe, it is clear that leaders in dominant societies have failed to control the human activities driving climate change and habitat loss, while Indigenous lands and waters have been successfully taken care of over millennia 80 . In Canada, Brazil and Australia, for instance, vertebrate biodiversity in Indigenous territories equals or surpasses that found within formally protected areas.

Indigenous approaches to conservation regularly place reciprocal people-place relationships at the centre of cultural and care practices. These approaches hinge on systems of Indigenous knowledge which include scientific and ecological understandings that are carried across generations through language, story, ceremony, practice and law.

With a fundamental, system-wide reorganisation across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values, there might still be a chance that we can reverse the trend of nature’s decline.

Economics, at its core, is the study of how people make choices under conditions of scarcity, and of the consequences of those choices for society. Simply put, we need to move to an economy that values well-being in its diverse forms, not only monetary, and one which is fully responsive to resource scarcity.

A global goal of reversing biodiversity loss to secure a nature-positive world by 2030 is necessary if we are to turn the tide on nature loss and safeguard the natural world for current and future generations. It must be our guiding star, in the same way that the goal of limiting global warming to 2°C, and preferably 1.5°C, guides our efforts on climate.

Recognition of the integrated nature of our environmental challenges in turn enables the search for win-win solutions. Again, the science is clear: immediate action to reverse biodiversity loss is essential if we are to succeed in limiting climate change to 1.5°C; and climate change is expected to become a dominant driver of biodiversity loss if left unchecked.

It will only be through identifying and pursuing solutions that tackle these connected challenges while also benefiting people that we will be able to course-correct and secure a healthier natural world, to help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

Citation

WWF (2022) Living Planet Report 2022 - Building a nature-positive society. Almond, R.E.A., Grooten, M., Juffe Bignoli, D. & Petersen, T. (Eds). WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

Land resources – soil, water, and biodiversity – provide the foundation for the wealth ofour societies and economies. They meet the growing needs and desires for food, water,fuel, and other raw materials that shape our livelihoods and lifestyles. However, theway we currently manage and use these natural resources is threatening the health andcontinued survival of many species on Earth, including our own.

Of nine planetary boundaries used to define a ‘safe operating space for humanity’, fourhave already been exceeded: climate change, biodiversity loss, land use change, and geochemical cycles. These breaches are directly linked to human-induced desertification, land degradation, and drought. If current trends persist, the risk of widespread, abrupt, or irreversible environmental changes will grow.

Tracking the health of nature over almost 50 years, the Living Planet Index acts as an early warning indicator by tracking trends in the abundance of mammals, fish, reptiles, birds and amphibians around the world. In its most comprehensive finding to date, this edition shows an average 69% decline in the relative abundance of monitored wildlife populations around the world between 1970 and 2018.

Roughly USD 44 trillion of economic output – more than half of global annual GDP– is moderately or highly reliant on natural capital. Yet governments, markets, and societies rarely account for the true value of all nature’s services that underpin human and environmental health. These include climate and water regulation, disease and pest control, waste decomposition and air purification, as well as recreation and cultural amenities.

Conserving, restoring, andusing our land resources sustainably is a global imperative: one that requires moving to acrisis footing.

At no other point in modern history has humanity faced such an array of familiar and unfamiliar risks and hazards, interacting in a hyper-connected and rapidly changing world. We cannot afford to underestimate the scale and impact of these existential threats. Rather we must work to motivate and enable all stakeholders to go beyond existing development and business models to activate a restorative agenda for people, nature, and the climate.

Land restoration is essential and urgently needed. It must be integrated with allied measures to meet future energy needs while drastically reducing greenhouse gasemissions; address food insecurity and water scarcity while shifting to more sustainable production and consumption; and accelerate a transition to a regenerative, circular economy that reduces waste and pollution.

Restoration is a proven and cost-effective solution to help reverse climate change and biodiversity loss caused by the rapid depletion of our finite natural capital stocks.

Land restoration is broadly understood as a continuum of sustainable land and water management practices that can be applied to conserve or ‘rewild’ natural areas, ‘up-scale’ nature-positive food production in rural landscapes, and ‘green’ urban areas, infrastructure, and supply chains.

The land restoration agenda is a multiple benefits strategy that reverses past land and ecosystem degradation while creating opportunities that improve livelihoods and prepareus for future challenges.

Land is the operative link between biodiversity loss and climate change, and therefore must be the primary focus of any meaningful intervention to tackle these intertwined crises. Restoring degraded land and soil provides the most fertile ground on which to take immediate and concerted action.

Land and ecosystem restoration will help slow global warming, reduce the risk, scale, frequency, and intensity of disasters (e.g., pandemics, drought, floods), and facilitate the recovery of critical biodiversity habitat and ecological connectivity to avoid extinctions and restore the unimpeded movement of species and the flow of natural processes that sustain life on Earth.

Restoration is needed in the right places and at the right scales to better manage interconnected global emergencies. Responsible governance and land use planning will be key to protecting healthy and productive land and recuperating biodiverse, carbon-rich ecosystems to avoid dangerous tipping points.

Modern agriculture has altered the face of the planet more than any other human activity– from the production of food, animal feed, and other commodities to the marketsand supply chains that connect producers to consumers.

Making our food systems sustainable and resilient would be a significant contribution to the success of the global land, biodiversity, and climate agendas.

Globally, food systems are responsible for 80% of deforestation, 70% of freshwater use, and are the single greatest cause of terrestrial biodiversity loss.

At the same time, soil health and biodiversity below ground – the source of almost all our food calories – has been largely neglected by the industrial agricultural revolution of the last century.

Intensive monocultures and the destruction of forests and other ecosystems for food and commodity production generate the bulk of carbon emissions associated with land use change. Nitrous oxides from fertilizer use and methane emitted by ruminant livestock comprise the largest and most potent share of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions

Top-down solutions to avoid or reduce land degradation and water scarcity are unlikely to succeed without bottom-up stakeholder engagement and the security of land tenure and resource rights.

At the same time, trusted institutions and networks are needed tohelp build bridges that bring together different forms of capital to restore land health and create dignified jobs.

More inclusive and responsible governance can facilitate the shift to sustainable land use and management practices by building human and social capital.

Increased transparency and accountability are prerequisites for integrated land use planning and other administrative tools that can help deliver multiple benefits at various scales while managing competing demands.

Redirecting public spending towards regenerative land management solutions offers a significant opportunity to align private sector investment with longer-term societal goals– not only for food, fuel, and raw materials, but also for green and blue infrastructure for drought and flood mitigation, renewable energy provision, biodiversity conservation, and water and waste recycling.

Territorial and landscape approaches can leverage public and private financing for large-scale or multi-sector restoration initiatives by allowing diverse groups of stakeholders to establish partnerships that pool resources, aggregate project activities, and share costs. These collaborative approaches will make land restoration initiatives more effective and attractive to donors and investors.

The stark implications of the business-as-usual scenario means that decisive action at all levels and from all actors is needed to realize the promise of the restoration scenarios contained in this Outlook.

What is clear and unequivocal is the need for coordinated measures to meaningfully slow or reverse climate change, land degradation, and biodiversity loss to safeguard human health and livelihoods, ensure food and water security, and leave a sustainable legacy for future generations.

Ambitious land restoration targets must be backed by clear action plans and sustained financing. Countries that are disproportionately responsible for the climate, biodiversity, and environmental crises must do more to support developing countries as they restoretheir land resources and make these activities central to building healthier and more resilient societies.

The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration is galvanizing indigenous peoples and local communities, governments, the private sector, and civil society as part of a global movement to undertake all types of restoration, across all scales, marshalling all possible resources. This powerful 10-year ambition aims to transform land and water management practices to meet the demands of the 21st century while eradicating poverty, hunger, and malnutrition.

Citation

United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, 2022. The Global Land Outlook,second edition. UNCCD, Bonn.

Countries need to deliver on their existing commitments to restore 1 billion hectares of degraded land and make similar commitments for marine and coastal areas.

The world’s ecosystems – from oceans to forests to farmlands – are being degraded, in many cases at an accelerating rate. People living in poverty, women, indigenous peoples and other marginalized groups bear the brunt of this damage, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only worsened existing inequalities.

While the causes of degradation are various and complex, one thing is clear: the massive economic growth of recent decades has come at the cost of ecological health.

Ecosystem restoration is needed on a large scale in order to achieve the sustainable development agenda.

The conservation of healthy ecosystems – while vitally important – is now not enough. We are using the equivalent of 1.6 Earths to maintain our current way of life, and ecosystems cannot keep up with our demands. Simply put, we need more nature.

Half of the world’s GDP is dependent on nature, and every dollar invested in restoration creates up to USD 30 dollars in economic benefits.

Restoring productive ecosystems is essential to supporting food security. Restoration through agroforestry alone has the potential to increase food security for 1.3 billion people. Restoring the populations of marine fish to deliver a maximum sustainable yield could increase fisheries production by 16.5 million tonnes, an annual value of USD 32 billion.

Actions that prevent, halt and reverse degradation are needed if we are to keep global temperatures below 2°C. Such actions can deliver one-third of the mitigation that is needed by 2030. This could involve action to better manage some 2.5 billion hectares of forest, crop and grazing land (through restoration and avoiding degradation) and restoration of natural cover over 230 million hectares.

Large-scale investments in dryland agriculture, mangrove protection and water management will make a vital contribution to building resilience to climate change, generating benefits around four times the original investment.

With careful planning, restoring 15 per cent of converted lands while stopping further conversion of natural ecosystems could avoid 60 per cent of expected species extinctions.

Adopting inclusive wealth as a more accurate measure of economic progress. This will rest on the widespread introduction of natural capital accounting.

Increasing the amount of finance for restoration, including through the elimination of perverse subsidies that incentivize further degradation and fuel climate change, and through initiatives to raise awareness of the risks posed by ecosystem degradation

Taking action on food waste, making more efficient use of agricultural land, and encouraging a shift to a more plant-based diet.

Expanding awareness of the importance of healthy ecosystems throughout our educational systems.

The restoration of ecosystems at scale is no small task, and it will take a concerted effort to truly restore the planet. The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration aims to catalyse a global movement among local communities, activists, women, youth, indigenous groups, private companies, financial investors, researchers and governments at all levels.

Citation

United Nations Environment Programme (2021). Becoming #GenerationRestoration: Ecosystem restoration for people, nature and climate. Nairobi.